Extremist beliefs leading to violent and terrorist acts remain a severe threat to security in Europe. During 2020, in the Member States of the European Union alone, 57 terrorist attacks were reported, including completed, failed and foiled attempts. Twenty-one people died, and more than four hundred individuals were arrested (Europol, 2021).

These individuals imprisoned for terrorist offences and inmates who radicalise in prison pose a threat both during their imprisonment and after release (Europol, 2020). In 2020, at least five terrorist attacks in Europe had the involvement of released convicts or of prisoners at the time they committed the attack. (Europol, 2021).

Prison and probation structures have a crucial responsibility in preventing and countering violent extremism. The rehabilitation process of this massive number of radicalised individuals entering the system every year is essential to avoid recidivism once they are released. Even if successful in rehabilitation, proper reintegration into society is essential to avoid future re-radicalisation (RAN, 2016). On the other hand, if proper measures are not in place, the prison environment can exacerbate previous vulnerabilities in predisposed inmates and become a hotbed for radicalisation.

Nevertheless, the arduous rehabilitation process for these individuals is an uphill battle, full of difficulties and uncertainties. There is no definitive guide to disengagement and deradicalisation. Each combination of person, beliefs and particular path to extreme viewpoints is unique. Any rehabilitation initiative must holistically approach each case’s specificity and vulnerabilities.

If we are to mitigate radicalisation effectively, we need to understand the phenomena in depth.

The sources of radicalised viewpoints include diverse positions on different spectrums and ideologies: Jihadist, Right-wing, Left-wing, Anarchist, Ethno-nationalist and separatist beliefs, and even State-sponsored terrorism. These different extremist origins have their own characteristics and particularities that experts and practitioners must be aware of and understand. Better knowledge means early identification of radicalisation cases and a subsequent evaluation, disengagement/deradicalisation and reintegration measures adjusted to the subject’s reality.

A focus on Far-right – Threats and trends

Far-right extremist ideology develops from a core of nationalism, white supremacism and neo-fascism, with a strong islamophobic, antisemitic, anti-immigration racist rhetoric and an overall resistance against diversity and equality.

In addition to longstanding active neo-Nazi groups, a growing threat has been identified in self-radicalised suspects of young age, including minors (Europol, 2021). These individuals connect transnationally on online channels and forums of varying degrees of organisation (Europol, 2021).

This online presence is standard practice across the board for far-right extremism. One example is the proliferation of online disinformation, which creates a false mirror of the world. Facts are easily distorted, disseminated and assimilated with no confirmation or counterpoint. These virtual spheres create a normalisation of hate speech and intolerance.

Another defining characteristic of this type of extremism across Europe is the interest in weapons and paramilitary combat training (Europol, 2021). This trend falls in line with the belief of opposition to “the system” and accelerationist movements that seek the fall of the existing political and social system (Europol, 2021).

Far-right extremism in the Balkans and Eastern Europe

When speaking of far-right trends in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, we must account for the prejudiced mentality already rooted in a substantial portion of its community. There is a present and exploitable discrimination against migrants and even fellow residents of other ethnicities such as the Roma population.

In Romania, this overall atmosphere of intolerance is widespread in politics, popular culture and everyday life, legitimising extreme nationalism and discrimination towards selected groups (Cinpoes, 2013). In the last decades, the Roma population and homosexuals have become some of the top targets of prejudice (Turcanu, 2010).

In Balkan countries affected by the migration crisis, namely Bulgaria or Slovenia, vigilante groups arose as a reaction to the migrant influx. These organised groups, built under the guise of protection of the population, are based on popular prejudices and fear and can lead to radicalisation and justification of violence (Stoynova & Dzhekova, 2019; EUROPOL 2020).

In Slovenia, these anti-migrant far-right groups use social media to recruit members and provide weapon training and military techniques (EUROPOL 2020).Along with the growth of far-right groups, this emergence of paramilitary factions is a security threat for the country (Bulc, 2021; EUROPOL 2020).

The aforementioned radicalisation of young people in internet groups is a growing concern for Bulgaria (Europol, 2021). Studies suggest that youngsters angry with social inequalities and still developing their identity might be more accepting of nationalist ideas (Mancheva et al., 2015).

In Serbia, several factors fuel the far-right: economic hardship, crises of identity and democracy, ethnic conflict, and other historical influences such as the fallout of former Yugoslavia and the close link between the State and Orthodox Church (Klacar et al., 2018). The 2015 European migrant and refugee crises also revived authoritarian and nationalist viewsin the country (Klacar, 2020).

Sharing knowledge among experts and practitioners

Uniting European knowledge and efforts, project HOPE wants to improve radicalisation prevention and countering results with a focus on Balkan and Eastern Europe countries. The consortium is developing a growing network that supports continuous training, sharing of information and experience on P/CVE.

By bringing together this European network and stimulating their interaction, HOPE expects to improve the overall success of practitioners in P/CVE. These professionals will be able to support their work on an extensive information pool, with established and proven knowledge developed by partnering transnational experts.

HOPE’s Transnational Thematic Workshops (TTWs) are a materialisation of this network that approach topics in the project’s field, exploring theoretical and practical content. The third event, out of the eight planned TTWs, gathered over sixty global experts and practitioners to discuss new and established far-right extremist trends.

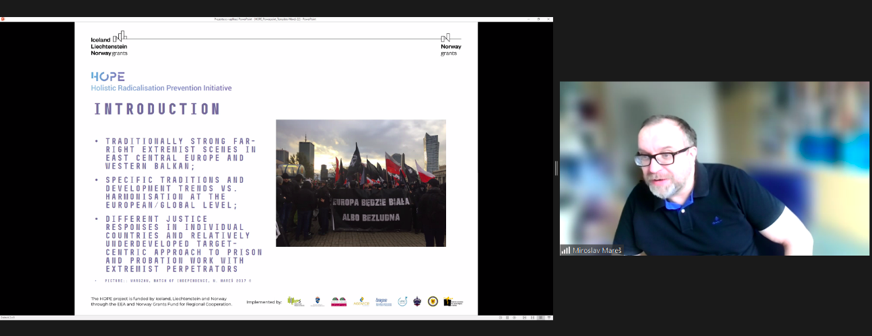

In this event, Professor Miroslav Mareš, an expert in Political Sciences from Czech Republic’s Masaryk University, emphasised the “new face” of far-right extremism. Now associated with the stand against COVID-19 restrictions and measures, the movement’s agenda was refreshed and reached new audiences.

Besides, the Professor shared practical examples of far-right extremist cases in the targeted region, enveloping trends and concerns identified in the region.

When the “extreme” becomes “normal”

Moreover, the normalisation of the far-right rhetoric in Eastern Europe through its growing representation in higher politics is a concern emphasised by Professor Miroslav Mareš. This rise of populist nationalism is taking place across Europe partly benefited from the severe migration crisis of the last years, which has been instrumentalised to instil prejudices and anti-migration sentiment.

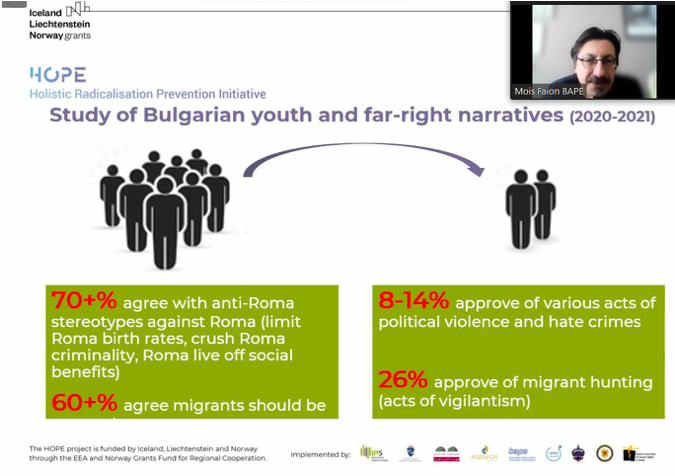

Speaking of the Bulgarian reality, Mois Faion, chairman of the Bulgarian Association for Policy Evaluation (BAPE) and expert on Policy Evaluation and Security, also highlighted the dangers of the normalisation of far-right rhetoric in the country.

Mois Faion presented worrisome data that emphasises how the majority of the Bulgarian population share anti-Roma and anti-migrant attitudes. A considerable fraction (8-14%) even agrees with violent acts over social minorities.

The role of inter-agency cooperation in radicalisation prevention

The radicalised individual’s violent mindset makes continuous risk assessment crucial. However, events such as the transition between prison and probation contexts and the multitude of professional roles involved in the process make the results of P/CVE efforts hard to follow and evaluate. Accompanying these developments is critical to understanding the threat scale and ensuring the adjustment of future radicalisation prevention and countering efforts.

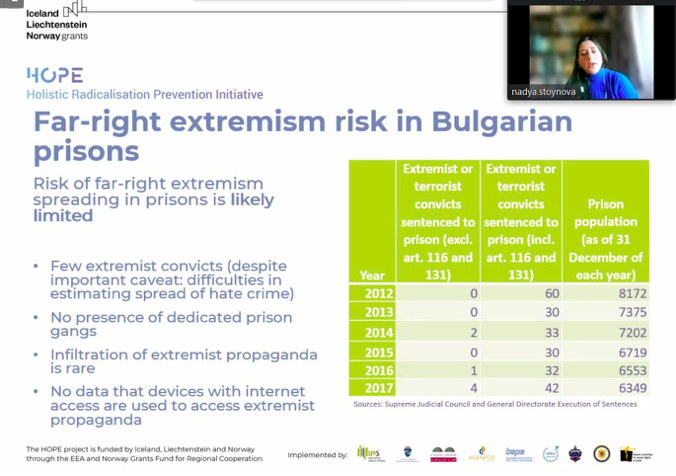

Focusing on the implications of the data presented and discussed for criminal justice, Nadya Stoynova, a specialist in prison and probation radicalisation, stressed the importance of sustained risk assessment and intervention approaches.

Nadya Stoynova from the Bulgarian Association for Policy Evaluation, provided a thorough overview of the risks of far-right extremism in prison and probation in the Bulgarian reality, focusing on its trends, problems and potentialities.

This BAPE representative underlines that a trustworthy and functional evaluation must comprise data from a continuous effort between prison and probation settings, reinforcing the relevance of inter-agency cooperation.

This third Transnational Thematic Workshop was also an opportunity to debate entertainment as a booster for far-right extremism, its risks and intervention potentialities, with a particular focus on the community setting.

In this debate, participants also highlighted the critical role community stakeholders have in facilitating the disengagement of far-right extremism. The discussion led to sharing of some known good practices from NGOs to promote a sustained prison-community continuum.

What is next for HOPE?

The last online Transnational Thematic Workshops is set to happen on March 11, 2022 and will discuss multi-agency cooperation in P/CVE. The project consortium hopes to continue engaging a large number of participants and building knowledge on radicalisation prevention as a European network. Hopefully, the last four planned events will be presential and allow for even more substantial involvement between the participants.

The HOPE Initiative is led by IPS_Innovative Prison Systems (Portugal) in partnership with the University College of Norwegian Correctional Service (Norway),Agenfor International Foundation (Italy), the Euro-Arab Foundation for Advanced Studies (Spain), the Bulgarian Association for Policy Evaluation, the Bulgarian General Directorate “Execution of Sentences”, the Bucharest-Jilava Penitentiary (Romania), the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights (Serbia) and the Slovenian Probation Administration (Ministry of Justice).

For more information about the HOPE project, please visit its website.

References

Bulc, G. (2021). Deradicalization and Integration Legal and Policy Framework.

Cinpoes, R. (2013). Country analyses: Romania. In R. Melzer & S. Serafin, Right-wing extremism in Europe: Country analyses, counter-strategies and labour-market oriented exit strategies, 169-198, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Frankfurt;

EUROPOL (2020). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

EUROPOL (2021). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Klacar, B. (2020, August 4). Serbia’s Right-Wing Shift Risks Fuelling Extremism. Balkan Insight. https://balkaninsight.com/2020/08/04/serbias-right-wing-shift-risks-fuelling-extremism/

Klacar, B., Čolović, I., Marković, A., & Orestijević, E. (2018). Assessment of Violent Extremism in Serbia. Center for Free Elections and Democracy. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TH7V.pdf

Mancheva, R., M., Doichinova, M., Derelieva, L., Bezlov, T., Karayotonva, M., Tomov, Y., Markov, D. & Ilcheva, M. (2015). Radicalisation in Bulgaria: Threats and trends. Center for the Study of Democracy.

RAN (2016). Approaches to violent extremist offenders and countering radicalisation in prisons and probation. Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN). https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/271624/ran_pp_approaches_to_violent_extremist_en.pdf?sequence=1

Stoynova, N. & Dzhekova, R. (2019). Vigilantism against ethnic minorities and migrants in Bulgaria. In T. Bjørgo & M. Mareš, Vigilantism against migrants and minorities, pp. 164-182, Routledge: Oxon.

Turcanu, F. (2010). Right-wing extremism and its impact on young democracies in the CEE-countries. State, society, NGOs on right-wing extremism in Romania. Paper for the conference “Right-Wing Extremism in CEE-countries. Strategies against Right-wing extremism, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Budapest, 19-November, 2010